Akbar Šáh II.

| Akbar Šáh II. | |

|---|---|

| mughalský císař | |

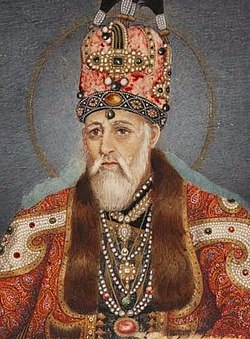

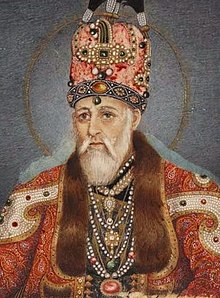

Portrét korunovaného Akbara Šáha II., kolem 1827 | |

| Doba vlády | 19. listopad 1806 – 28. září 1837 |

| Úplné jméno | Akbar Šáh II. Zafar |

| Narození | 22. duben 1760 Mukundpur, Satná |

| Úmrtí | 28. září 1837 Dillí |

| Pohřben | Zafar Mahal, Mehrauli |

| Předchůdce | Alam Šáh II. |

| Nástupce | Bahádur Šáh II. |

| Manželky | Lal Bai Selaa'h-un-Nissa Gumani Khanum |

| Potomci | 14 synů, 8 dcer |

| Dynastie | Mughálská |

| Otec | Alam Šáh II. |

| Některá data mohou pocházet z datové položky. | |

Akbar Šáh II. (22. dubna 1760 Mukundpur, okres Satná – 28. září 1837 Dillí) byl 17. (předposlední ) indický císař mughálské dynastie. Oficiálně vládl v letech 1806 až 1837, fakticky spoluvládl se svým slepým otcem již před rokem 1799. Byl druhým synem šáha Alama II. a otcem šáha Bahádura II. Akbarovu moc omezoval rostoucí britský vliv v Indii, především prostřednictvím Východoindické společnosti (East Indian Company).

Život

Princ jménem Mirza Akbar se narodil 22. dubna 1760 jako druhý syn císaře Alama Šáha II. v Mukundpuru v Satně, zatímco jeho otec byl v exilu. Po smrti svého staršího bratra dne 2. května 1781 v Červené pevnosti v Dillí jmenován korunním princem. V letech 1782–1799 byl místokrálem Dillí. Když renegátský eunuch Ghulam Qadir ovládl Dillí, byl princ Mirza Akbar společně s dalšími mughalskými knížaty a princeznami donucen tančit na jeho dvoře. Byl účasten ponížení a hladovění celé císařské rodiny Mughalů. Když Šáh Džahán IV uprchl, Mirza Akbar byl jmenován titulárním císařem s titulem Akbar Šáh II. a měl zůstat v úřadu až do návratu svého otce v lednu 1789.

Císař vládl říši omezené na Červenou pevnost v Dillí. Odmítl se podřídit úředníkům Východoindické společnosti, jejich lordu Hastingsovi odmítl poskytnout audienci k vyjednávání jiných podmínek než s vlastním postavením suveréna. Britové proto v roce 1835 omezili jeho titulární autoritu na „krále Dillí“ a Východoindická společnost přestala fungovat jako dosud. Současně Britové nabídli královské tituly Nawabovi z Oudhu a Nizámovi z Hajdarábádu, aby dále omezili Akbarovu vládu. Nawab titul přijal. V roce 1835 přestala dosud jen obchodní Východoindická společnost respektovat vládu indického císaře, přestala razit mince s jeho jménem a perským nápisem a odvádět mincovní regál. Akbar II. proti bezpráví Východoindické společnosti angažoval bengálského reformátora Ram Mohan Roye, který jako jeho vyslanec jednal v Anglii a podal žalobu u soudu, ale bezvýsledně.

Poklad

Britové si za jeho vlády nedovolili přisvojit poklad zlata a drahokamů mughálské dynastie (ve starší české literatuře zvaný Poklad velkých mogulů). Symbolem jejich pohádkového bohatství byl císařský Paví trůn, zdobený figurkami pávů s raritními drahokamy v očích a v ocase, císařská koruna, množství náhrdelníků a dalších šperků a gem s rytými nápisy.

Hrobka

Zděná kupolová hrobka stojí v Zafar Mehralu, obec Mehrauli v jižním okolí Dillí; šáhův mramorový hrob leží vedle hrobu súfijského svatého Qutbuddina Bakhtiara Kakiho (1173–1235).

Odkazy

Literatura

- Encyclopaedia Indica: Akbar Shah II, , Anmol Publications, New Delhi 1999.

- Hans-Georg Behr: Die Moguln. Macht und Pracht der indischen Kaiser von 1369–1857. Econ Verlag, Wien-Düsseldorf 1979.

- Lord Roberts of Kandahár: Ein und vierzig Jahre in Indien. Berlin 1904, I. díl (dostupné online[1] německy), II. díl

Externí odkazy

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Akbar Šáh II. na Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Akbar Šáh II. na Wikimedia Commons

Média použitá na této stránce

Akbar Shah II of India.

The Delhi Darbar of Akbar II.

In this painting attributed to the artist Ghulam Murtaza Khan, the Mughal emperor Akbar II (r. 1806-37 CE) holds court from atop an exquisite, jewel-encrusted jharoka, or throne, covered by a baldachin and topped with an embroidered canopy; the jharoka is a copy of the famous Peacock Throne looted by the Iranians under the Afsharid ruler Nadir Shah (r. 1736-47 CE) in 1738-39 CE. Akbar’s sons, Abu Zafar Siraj al-Din (the future Bahadur Shah II and the last ruler of the Mughal dynasty, r. 1838-57 CE), Mirza Salim, Mirza Jahangir and Mirza Babur, stand in attendance on either side of their father. They are visually distinguished from the two barefoot servants flanking the scene by their dress, their situation on the royal red carpet, and their closer proximity to Akbar, whose figure fills the centre of the picture plane.The scene represents a continuation of the Mughal practice of darshan, the presentation ceremony for the Mughals, into the nineteenth century. Darshan reflected a merging of the Hindu practice of that name, meaning “beholding,” with the notion of the king being accessible to his subjects and imparting auspicious blessings to them in the same manner a deity’s image would to its beholder (Asher 1993, p. 282). The Mughal adoption of the darshan ritual from Hindu culture enhanced the rulers’ semi-divine image, alluded to in paintings such as this one by the glowing halo around the ruler’s head. The setting in which Akbar II appears is known as the jharoka-i khass-u-?amm, where the ruler would hold court and take care of administrative duties. The darbar, or assembly, could consist of all classes of people, from family members and court grandees to the general public (hence khass-u-?amm, or “high and low”) (Koch 1997, p. 133).

The level of portraiture and detail is exceedingly fine in this painting of a darbar scene. The faces are depicted with subtle shading and highly individualistic features such as the light beards, rounded chins or in the case of the old emissary at right, sunken cheeks. The scene likely takes place in the winter because of the warm clothing, turbans, and headdresses shown.

Compare to a larger gathering depicted in E. Smart and D. Walker, Pride of the Princes: Indian Art of the Mughal Era in the Cincinnati Art Museum, 1985, cat. no. 19. and to T. Falk and M. Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, 1981, no.227i. E. Smart notes that there are eight similar known darbar pictures, with some also depicting British emissaries. Inscriptions in the other paintings allow the identification of the princes from left to right: Abu Zafar Siraj ud-Din (heir apparent Bahadur Shah II), Mirza Salim, Mirza Jahangir, and Mirza Bahadur. Though not all of the Darbar paintings were by the hand of Ghulam Murtaza Khan, based on the India Office Library painting, one can attribute this painting to him.

Though the Mughal Empire was disintegrating, Smart also remarks that the early 19th century was a high point in the production of high quality painting. The artist was successful in capturing the glittering sophistication and decadence of the court, which juxtaposed with the anxious expressions on the principal figures, poignantly evoke the waning Mughal era.

Materials and technique: Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper

Dimensions: 39.4 x 30.9 cm

Aga Khan Museum Accession number AKM00214. Auctioned at Christie's in 2001 for US$28,200. Previously property from a New England Collection.The Tombs of Shah Alam and Akbar II," a gelatin silver photo, c.1890's