Astronomický objekt

| |||||||

| Výběr některých astronomických objektů |

Astronomický objekt (též nebeský nebo kosmický objekt) je přirozeně se vyskytující hmotný objekt, útvar nebo struktura, kterou můžeme pozorovat za hranicí zemské atmosféry, v pozorovatelném vesmíru.[1][2][3] Astronomické objekty jsou tak hlavním předmětem zkoumání v astronomii a astrofyzice.

Astronomické těleso (též nebeské těleso) je astronomický objekt, který je jasně ohraničen a tvoří jej pevně spojené gravitačně vázané celistvé těleso. Příkladem astronomických těles mohou být planetky, měsíce, planety a hvězdy.

Astronomické objekty mohou být i gravitačně méně soudržné struktury, jejichž společnou vlastností je určitá pozice v prostoru, ale mohou se skládat z většího počtu astronomických těles nebo i jiných objektů s dílčími strukturami.[1] Příkladem astronomických objektů (mimo tělesa) mohou být prstence u planet, hvězdokupy, mlhoviny nebo celé galaxie. Kometu lze označit za těleso i objekt: Kometa je tělesem, pokud se jedná o zmrzlé jádro z ledu a prachu, a objektem, pokud se popisuje celá kometa s jádrem, rozptýlenou komou a ohonem komety.

Klasifikace astronomických objektů

Na vesmír lze pohlížet jako na hierarchickou strukturu. Pojmem struktura je míněn každý objekt, který je držen dohromady gravitací. Takových objektů je ve vesmíru velké množství a jsou značně různorodé. V největších (tzv. kosmologických) měřítkách je základní složkou vesmíru galaxie. Galaxie jsou uspořádány do skupin a kup, často v rámci větších nadkup, které jsou seskupeny podél velkých vláken mezi téměř prázdnými dutinami a vytvářejí kosmickou síť, která se táhne celým pozorovatelným vesmírem.[4][5]

Astronomické objekty, jako jsou hvězdy, planety, mlhoviny, planetky a komety, jsou pozorovány již tisíce let. Astronomové se již od počátku snažili tyto nebeské objekty klasifikovat. Prvním krokem je vždy objev, následně pozorování a klasifikace pozorovaných objektů. Již staří Řekové rozlišovali "stálé hvězdy" (αστερία) a "pohyblivé hvězdy" (πλανήτης). Ty byly většinou spojovány s bohy a počínaje Platónem v jeho dialogu Tímaios poskytly první matematické modely nebeských jevů. Dějiny astronomie ukazují, že pojmy objevování a klasifikace jdou ruku v ruce, protože nutkání klasifikovat objevy nových objektů se zdá být nedílnou součástí lidské mysli. Stejně tak se klasifikace může díky novým poznatkům a technikám změnit. [6] Astronomové se mohou z podobných analýz i v jiných vědách hodně naučit, jak bylo patrné při diskusích o planetě Pluto v roce 2006 na valném shromáždění Mezinárodní astronomické unie v Praze.

Přestože nejstarší klasifikační systémy hvězd a galaxií v astronomii jsou staré sotva více než jedno století, snaha o hledání nových tříd astronomických objektů se datuje ještě dříve. Giovanni Hodierna v polovině sedmnáctého století klasifikoval mlhavé objekty pozorované galileovským refraktorovým dalekohledem do tří tříd: "Luminosae" (hvězdokupy, viditelné pouhým okem), "Nebulae" (objekty vypadající jako mlhoviny, ale v dalekohledu rozlišitelné)) a "Occultae" (objekty nerozlišitelné ani dalekohledem). [7][8] O sto let později sestavil Charles Messier rozsáhlejší seznam mlhovin, hvězdokup a galaxií, ale o klasifikaci se nepokusil. Snaha o hledání nových tříd astronomických objektů se datuje, podobně jako Linnéova klasifikace v biologii, do osmnáctého století, zejména v práci Williama Herschela. Kromě objevu Uranu v roce 1781 a zavedení termínu "asteroid" pro novou třídu objektů objevených v roce 1801 odhalil Herschel při prohlídkách oblohy svými velkými dalekohledy obrovské množství mlhovin, které se podle jeho názoru nacházely v různých stadiích růstu a vývoje. Herschel ve svém díle opakovaně používal při klasifikaci objektů biologickou analogii, kterou v devatenáctém století převzali takoví průkopníci přírodovědy, jako byl např. Alexander von Humboldt, a setkáváme se s ní i v moderní astronomii.

V 19. a 20. století umožnily nové technologie a vědecké inovace vědcům výrazně rozšířit znalosti o astronomii a astronomických objektech. Začaly se stavět větší dalekohledy a observatoře a vědci začali zobrazovat snímky Měsíce a dalších nebeských těles na fotografické desky. Byly objeveny nové vlnové délky světla, které lidské oko nevidí, a byly vyrobeny nové dalekohledy, které umožnily pozorovat astronomické objekty i v jiných vlnových délkách spektra. Také klasifikace komet byla v 19. století významným počinem: Stephen Alexander (1850)[9] uvažoval o dvou skupinách na základě velikosti oběžných drah, Dionysius Lardner (1853)[10] navrhl tři skupiny oběžných drah a E. Barnard (1891)[11] je rozdělil do dvou tříd na základě morfologie.

Kromě segmentace jasných hvězd do souhvězdí byla většina hvězdných klasifikací založena na barvách a spektrálních vlastnostech hvězd. V 60. letech 19. století klasifikoval průkopník spektroskopie Angelo Secchi hvězdy do pěti tříd: bílé, žluté, oranžové, uhlíkové a hvězdy s emisní čarou. Po mnoha debatách byla později hvězdná spektrální posloupnost upřesněna skupinou na Harvardu na známé spektrální typy O, B, A, F, G, K, M, o nichž se později zjistilo, že jsou posloupností na základě povrchové teploty.

Krátce poté, co potvrdil, že některé mlhoviny jsou vnější galaxie, navrhl Edwin Hubble svou slavnou rozvětvenou klasifikaci galaxií se třemi třídami: eliptické, spirální a nepravidelné. Tyto třídy později upřesnil a rozvinul Gerard de Vaucouleurs [12]. Supernovy, které se téměř všechny nacházejí mimo naši Galaxii, mají klasifikační schéma vycházející z čar chemických prvků, objevujících se v jejich hvězdném spektru, a podle tvaru světelné křivky. Clive Tadhunter (2008)[13] uvádí trojrozměrnou klasifikaci aktivních galaktických jader zahrnující zářivý výkon, šířku emisní čáry a svítivost jádra.

Tyto taxonomie sehrály nesmírně důležitou roli ve vývoji astronomie, ale všechny byly vytvořeny heuristickými metodami. Mnohé z nich jsou založeny na kvalitativním a subjektivním hodnocení prostorových, časových nebo spektrálních vlastností. Kvalitativní, morfologický přístup k astronomickým studiím výslovně prosazoval např. Fritz Zwicky. Astronomové často studují problémy, kde jsou k dispozici značné předchozí znalosti. Mnohdy byl takto intenzivně studován omezený vzorek blízkých, jasných objektů v dané třídě. Tyto prototypy pak mohou sloužit jako "cvičné soubory" pro klasifikaci větších, méně dobře charakterizovaných vzorků. Takto vytvořené klasifikace jsou založeny na kvantitativních kritériích, ale tato kritéria byla vyvinuta subjektivním zkoumáním cvičných dat. V žádném případě nebyl k vymezení tříd objektů použit statistický nebo algoritmický postup. Používání cvičných sad, spolu s často sofistikovanými algoritmy pro monitorovanou klasifikaci, spadá pod pojem strojové učení.[14] Na základě zkušeností s projektem Galaxy Zoo vědci vyvinuli kódy pro strojové učení, které umožňují počítačům 90% shodu v klasifikaci galaxií ve srovnání s klasifikací člověka.[15]

Na rozdíl od biologie, fyziky a chemie, a navzdory dlouhé a význačné historii klasifikace konkrétních objektů, jako jsou hvězdy a galaxie, astronomie postrádá komplexní, široce přijímaný klasifikační systém objektů. Všechny klasifikační systémy objektů v astronomii jsou do jisté míry libovolné. Počet tříd astronomických objektů objevených od dob Herschelových mlhovin se značně rozšířil, některé se zdají být zřejmé, jako například komety, planetky, kvazary, pulsary a spirální galaxie. Jedním ze způsobů, jak přistoupit k otázce definice třídy, je podívat se do historie, kde (nehledě na výjimky jako hvězdy a galaxie) byla klasifikace často ad hoc, nahodilá a historicky podmíněná okolnostmi. Pokud astronomická historie něco ukazuje, pak to, že klasifikace astronomických objektů byla založena na mnoha charakteristikách v závislosti na stavu poznání a potřebách konkrétní komunity v dané době.[16]

Například planety se mohly dělit podle své fyzikální povahy (terestrické, plynní obři a ledoví obři) nebo, jak ukázaly nedávné objevy exoplanet, podle orbitálních charakteristik (vysoce eliptické nebo kruhové) či podle blízkosti k mateřské hvězdě (horké Jupitery) atd. Historicky byly dvojhvězdy často klasifikovány podle způsobu pozorování jako vizuální, spektroskopické, zákrytové a astrometrické, nebo - poté, co bylo známo více informací - podle konfigurace či obsahu systému či podle dominantní vlnové délky elektromagnetického záření, jako je tomu u rentgenových dvojhvězd. Přestože tyto překrývající se systémy astronomům dobře posloužily a ilustrují, jak lze tentýž objekt klasifikovat mnoha způsoby, jsou tato označení zdrojem mnoha nejasností, zejména pro neodbornou veřejnost.[16]

Historie také ukazuje, že v době objevu je někdy z podstaty problému obtížné rozhodnout, zda byla objevena nová třída objektů. Snad na základě analogie s naším Měsícem Galileo poměrně rychle rozhodl, že čtyři objekty, které poprvé spatřil v roce 1610 kroužit kolem Jupitera, jsou satelity, což byl důkaz, že Měsíc není jedinečný, ale patří do třídy cirkumplanetárních objektů (i když Galileo nehovořil v termínech třídy). Objekt, který poprvé spatřil kolem Saturnu, však vůbec nebyl zjevně prstenec a čekal na správný výklad Christiaana Huygense o více než 40 let později. Ještě před sto lety astronomové nedokázali rozlišit strukturu o rozloze 40 astronomických jednotek (např. Sluneční soustava) od struktury milionkrát větší (např. galaxie). Ani na konci 20. století nebylo hned zřejmé, že pulsary jsou neutronové hvězdy, nebo že kvazary jsou aktivní galaktická jádra, přičemž obojí se nakonec kvalifikovalo pro status nové třídy.

V průběhu několika desetiletí tak bylo vyvinuto mnoho menších klasifikačních systémů pro jednotlivé třídy objektů, od planetek a komet přes mlhoviny a hvězdokupy až po dvojhvězdy a supernovy. Každý z nich však byl formulován různými způsoby, které se ukázaly jako užitečné pro komunity, jež tyto objekty studují. Téměř nikdy však jejich klasifikátoři neměli na mysli konzistentní principy, které by platily napříč různorodými obory astronomie. Nejvíce se tomu přiblížil až astronom a historik vědy Steven Dick. Výsledkem jeho mnohaleté práce[6][16] je Astronomický klasifikační systém 3K.

V následující tabulce jsou uvedeny obecné kategorie astronomických těles a objektů podle jejich umístění nebo struktury, včetně hypotetických objektů.

Seznam hlavních skupin astronomických objektů

| Sluneční soustava | Objekty mimo sluneční soustavu | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Jednoduché objekty | Soustavy | Struktury | |

|

| ||

Související články

- Astronomický klasifikační systém 3K

- Kosmické těleso

- Označení astronomických objektů

Reference

- ↑ a b An Etymological Dictionary of Astronomy and Astrophysics [online]. Heydari-Malayeri, M. (Paris Observatory) [cit. 2024-03-07]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Naming Astronomical Objects [online]. Task Group on Astronomical Designations from IAU Commission 5, Duben 2008 [cit. 2024-01-29]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ A Multilingual on-line Dictionary of Astronomical Concepts [online]. Listopad 2009 [cit. 2024-03-19]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ COLES, Peter. Kosmologie (původním názvem: Cosmology: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2002)). Překlad Klimánek, O.. 1. vyd. [s.l.]: Dokořán, 2007. ISBN 9788073631611.

- ↑ KULHÁNEK, Petr. Jak vznikal svět. 1. vyd. [s.l.]: AGA, 2019. ISBN 9788090663817.

- ↑ a b DICK, Steven, J. Discovery and classification in astronomy : controversy and consensus. 1. vyd. [s.l.]: Cambridge University Press, 2013. Dostupné online. ISBN 9781139521499. (anglicky)

- ↑ FROMMERT, H.; KRONBERG, C. Giovanni Battista Hodierna (April 13, 1597 – April 6, 1660). messier.seds.org [online]. [cit. 2024-03-07]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ FODERA-SERIO, G.; INDORATO, L.; NASTASI, P. G.B. Hodierna's Observations of Nebulae and his Cosmology. S. 1–36. Journal for the History of Astronomy [online]. 1985. Čís. 16, s. 1–36. DOI 10.1177/002182868501600101. Bibcode 1985JHA....16....1F. S2CID 118328541.

- ↑ ALEXANDER, S. On the classification and special points of resemblance of certain of the periodic comets; and the probability of a common origin in the case of some of them. S. 147–150. Astronomical Journal [online]. 1850. Čís. vol. 1, iss. 19, s. 147–150. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1086/100098. Bibcode 1850AJ......1..147A. (anglicky)

- ↑ LARDNER, D. On the classification of comets and the distribution of their orbits in space. S. 188–191. [Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society] [online]. 1853. Čís. 13, s. 188–191. DOI 10.1093/mnras/13.6.188. Bibcode 1853MNRAS..13..188L. (anglicky)

- ↑ BARNARD, E. E. On a classification of the periodic comets by their physical appearance. S. 46. Astronomical Journal [online]. 1891. Čís. vol. 11, iss. 246, s. 46. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1086/101590. Bibcode 1891AJ.....11...46B. (anglicky)

- ↑ BUTA,R. J.; CORWIN, H. G.; ODEWAHN, S. C. The de Vaucouleurs atlas of galaxies. [s.l.]: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Dostupné online. ISBN 9780521820486. (anglicky)

- ↑ TADHUNTER, C. An introduction to active galactic nuclei: Classification and unification. S. 227–239. New Astronomy Reviews [online]. 2008. Čís. 52, Issue 6, s. 227–239. DOI 10.1016/j.newar.2008.06.004. Bibcode 2008NewAR..52..227T. (anglicky)

- ↑ FEIGELSON, Eric. Classification in Astronomy: Past and Present. 1. vyd. [s.l.]: Chapman & Hall, 2016. (Advances in Machine Learning and Data Mining for Astronomy). ISBN 9781138199309. (anglicky)

- ↑ BANERJI, M. A SPOL. Galaxy Zoo: reproducing galaxy morphologies via machine learning. S. 342–353. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society [online]. 2010. Čís. Vol.406, Issue 1, s. 342–353. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16713.x. Bibcode 2010MNRAS.406..342B. (anglicky)

- ↑ a b c DICK, Steven, J. Classifying the Cosmos: How We Can Make Sense of the Celestial Landscape. 1. vyd. [s.l.]: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019. ISBN 9783030103798. DOI 10.1007/978-3-030-10380-4. (anglicky)

Externí odkazy

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu astronomický objekt na Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu astronomický objekt na Wikimedia Commons

Média použitá na této stránce

Planetka (243) Ida se svým měsíčkem Dactylem

Description from NASA :

In this view captured by NASA's Cassini spacecraft on its closest-ever flyby of Saturn's moon Mimas, large Herschel Crater dominates Mimas, making the moon look like the Death Star in the movie "Star Wars."

Herschel Crater is 130 kilometers, or 80 miles, wide and covers most of the right of this image. Scientists continue to study this impact basin and its surrounding terrain (see PIA12569 and PIA12571).

Cassini came within about 9,500 kilometers (5,900 miles) of Mimas on Feb. 13, 2010. This mosaic was created from six images taken that day in visible light with Cassini's narrow-angle camera on Feb. 13, 2010. The images were re-projected into an orthographic map projection. This view looks toward the area between the region that leads on Mimas' orbit around Saturn and the region of the moon facing away from Saturn. Mimas is 396 kilometers (246 miles) across. This view is centered on terrain at 11 degrees south latitude, 158 degrees west longitude. North is up. This view was obtained at a distance of approximately 50,000 kilometers (31,000 miles) from Mimas and at a sun-Mimas-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 17 degrees. Image scale is 240 meters (790 feet) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://www.nasa.gov/cassini and http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.

Jupiter as seen by the space probe "Cassini". This is the most detailed global color portrait of Jupiter ever assembled. It is produced from several high resolution images taken a little more than a day before Cassini's closest approach to Jupiter.

This color photograph of the comet Kohoutek (C/1973 E1) was taken by members of the lunar and planetary laboratory photographic team from the University of Arizona, at the Catalina observatory with a 35mm camera on January 11, 1974.

The Sun photographed at 304 angstroms by the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA 304) of NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). This is a false-color image of the Sun observed in the extreme ultraviolet region of the spectrum.

Placed pointer to Sirius B

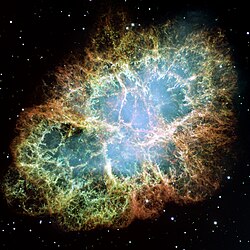

This is a mosaic image, one of the largest ever taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, of the Crab Nebula, a six-light-year-wide expanding remnant of a star's supernova explosion. Japanese and Chinese astronomers recorded this violent event in 1054 CE.

The orange filaments are the tattered remains of the star and consist mostly of hydrogen. The rapidly spinning neutron star embedded in the center of the nebula is the dynamo powering the nebula's eerie interior bluish glow. The blue light comes from electrons whirling at nearly the speed of light around magnetic field lines from the neutron star. The neutron star, like a lighthouse, ejects twin beams of radiation that appear to pulse 30 times a second due to the neutron star's rotation. A neutron star is the crushed ultra-dense core of the exploded star.

The Crab Nebula derived its name from its appearance in a drawing made by Irish astronomer Lord Rosse in 1844, using a 36-inch telescope. When viewed by Hubble, as well as by large ground-based telescopes such as the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, the Crab Nebula takes on a more detailed appearance that yields clues into the spectacular demise of a star, 6,500 light-years away.

The newly composed image was assembled from 24 individual Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 exposures taken in October 1999, January 2000, and December 2000. The colors in the image indicate the different elements that were expelled during the explosion. Blue in the filaments in the outer part of the nebula represents neutral oxygen, green is singly-ionized sulfur, and red indicates doubly-ionized oxygen.Autor: Event Horizon Telescope, uploader cropped and converted TIF to JPG, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Událost Horizon Telescope (EHT) - planetová škála osmi pozemních rádiových teleskopů kovaných prostřednictvím mezinárodní spolupráce - byla navržena tak, aby zachytila obrazy černé díry. V koordinovaných tiskových konferencích po celém světě vědci EHT odhalili, že uspěli a odhalili první přímý vizuální důkaz supermasivní černé díry v centru Messieru 87 a jeho stínu.

This image shows pulsed gamma rays from the Vela pulsar as constructed from photons detected by Fermi's Large Area Telescope. The Vela pulsar, which spins 11 times a second, is the brightest persistent source of gamma rays in the sky. The bluer colour in the latter part of the pulse indicates the presence of gamma rays with energies exceeding a billion electron volts (1 GeV). For comparison, visible light has energies between two and three electron volts. Red indicates gamma rays with energies less than 300 million electron volts (MeV); green, gamma rays between 300 MeV and 1 GeV; and blue shows gamma rays greater than 1 GeV. The image frame is 30 degrees across. The background, which shows diffuse gamma-ray emission from the Milky Way, is about 15 times brighter here than it actually is.

This stellar swarm is M80 (NGC 6093), one of the densest of the 147 known globular star clusters in the Milky Way galaxy. Located about 28,000 light-years from Earth, M80 contains hundreds of thousands of stars, all held together by their mutual gravitational attraction. Globular clusters are particularly useful for studying stellar evolution, since all of the stars in the cluster have the same age (about 12 billion years), but cover a range of stellar masses. Every star visible in this image is either more highly evolved than, or in a few rare cases more massive than, our own Sun. Especially obvious are the bright red giants, which are stars similar to the Sun in mass that are nearing the ends of their lives.

SMACS 0723-73 (1RXS J072319.7-732735, SMACS J0723.3-7327)

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has produced the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the distant universe to date. Known as Webb’s First Deep Field, this image of galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 is overflowing with detail.

Thousands of galaxies – including the faintest objects ever observed in the infrared – have appeared in Webb’s view for the first time. This slice of the vast universe is approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone on the ground.

This deep field, taken by Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), is a composite made from images at different wavelengths, totaling 12.5 hours – achieving depths at infrared wavelengths beyond the Hubble Space Telescope’s deepest fields, which took weeks.

The image shows the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago. The combined mass of this galaxy cluster acts as a gravitational lens, magnifying much more distant galaxies behind it. Webb’s NIRCam has brought those distant galaxies into sharp focus – they have tiny, faint structures that have never been seen before, including star clusters and diffuse features. Researchers will soon begin to learn more about the galaxies’ masses, ages, histories, and compositions, as Webb seeks the earliest galaxies in the universe.

This image is the telescope’s first-full color image released. It was released July 11, 2022 6:21PM (EDT).The Pleiades, an open cluster consisting of approximately 3,000 stars at a distance of 400 light-years (120 parsecs) from Earth in the constellation of Taurus. It is also known as ‘The Seven Sisters’, or the astronomical designations NGC 1432/35 and M45.

The Whirlpool Galaxy (Spiral Galaxy M51, NGC 5194), a classic spiral galaxy located in the Canes Venatici constellation, and its companion NGC 5195.

June 3, 2014

RELEASE 14-151

Hubble Team Unveils Most Colorful View of Universe Captured by Space Telescope

http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2014/27

Composite image showing the visible and near infrared light spectrum This is a composite image showing the visible and near infrared light spectrum collected from Hubble's ACS and WFC3 instruments over a nine-year period.

Astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have assembled a comprehensive picture of the evolving universe – among the most colorful deep space images ever captured by the 24-year-old telescope.

Researchers say the image, in new study called the Ultraviolet Coverage of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, provides the missing link in star formation. The Hubble Ultra Deep Field 2014 image is a composite of separate exposures taken in 2003 to 2012 with Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3. Astronomers previously studied the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (HUDF) in visible and near-infrared light in a series of images captured from 2003 to 2009. The HUDF shows a small section of space in the southern-hemisphere constellation Fornax. Now, using ultraviolet light, astronomers have combined the full range of colors available to Hubble, stretching all the way from ultraviolet to near-infrared light. The resulting image -- made from 841 orbits of telescope viewing time -- contains approximately 10,000 galaxies, extending back in time to within a few hundred million years of the big bang.

Prior to the Ultraviolet Coverage of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field study of the universe, astronomers were in a curious position. Missions such as NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) observatory, which operated from 2003 to 2013, provided significant knowledge of star formation in nearby galaxies. Using Hubble's near-infrared capability, researchers also studied star birth in the most distant galaxies, which appear to us in their most primitive stages due to the significant amount of time required for the light of distant stars to travel into a visible range. But for the period in between, when most of the stars in the universe were born -- a distance extending from about 5 to 10 billion light-years -- they did not have enough data.

"The lack of information from ultraviolet light made studying galaxies in the HUDF like trying to understand the history of families without knowing about the grade-school children," said principal investigator Harry Teplitz of Caltech in Pasadena, California. "The addition of the ultraviolet fills in this missing range."

Ultraviolet light comes from the hottest, largest and youngest stars. By observing at these wavelengths, researchers get a direct look at which galaxies are forming stars and where the stars are forming within those galaxies.

Studying the ultraviolet images of galaxies in this intermediate time period enables astronomers to understand how galaxies grew in size by forming small collections of very hot stars. Because Earth's atmosphere filters most ultraviolet light, this work can only be accomplished with a space-based telescope.

"Ultraviolet surveys like this one using the unique capability of Hubble are incredibly important in planning for NASA's James Webb Space Telescope," said team member Dr. Rogier Windhorst of Arizona State University in Tempe. "Hubble provides an invaluable ultraviolet light dataset that researchers will need to combine with infrared data from Webb. This is the first really deep ultraviolet image to show the power of that combination."

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington.

For Hubble Ultra Deep Field 2014 images and more information about Hubble, visit:

http://hubblesite.org/news/2014/27 and http://www.nasa.gov/hubbleJust weeks after NASA astronauts repaired the Hubble Space Telescope in December 1999, the Hubble Heritage Project snapped this picture of NGC 1999, a nebula in the constellation Orion. The Heritage astronomers, in collaboration with scientists in Texas and Ireland, used Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) to obtain the color image.

NGC 1999 is an example of a reflection nebula. Like fog around a street lamp, a reflection nebula shines only because the light from an embedded source illuminates its dust; the nebula does not emit any visible light of its own. NGC 1999 lies close to the famous Orion Nebula, about 1,500 light-years from Earth, in a region of our Milky Way galaxy where new stars are being formed actively. The nebula is famous in astronomical history because the first Herbig-Haro object was discovered immediately adjacent to it (it lies just outside the new Hubble image). Herbig-Haro objects are now known to be jets of gas ejected from very young stars.

The NGC 1999 nebula is illuminated by a bright, recently formed star, visible in the Hubble photo just to the left of center. This star is cataloged as V380 Orionis, and its white color is due to its high surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees Celsius (nearly twice that of our own Sun). Its mass is estimated to be 3.5 times that of the Sun. The star is so young that it is still surrounded by a cloud of material left over from its formation, here seen as the NGC 1999 reflection nebula.

The WFPC2 image of NGC 1999 shows a remarkable jet-black cloud near its center, resembling a letter T tilted on its side, located just to the right and lower right of the bright star. This dark cloud is an example of a "Bok globule," named after the late University of Arizona astronomer Bart Bok. The globule is a cold cloud of gas, molecules, and cosmic dust, which is so dense it blocks all of the light behind it. In the Hubble image, the globule is seen silhouetted against the reflection nebula illuminated by V380 Orionis. Astronomers believe that new stars may be forming inside Bok globules, through the contraction of the dust and molecular gas under their own gravity.

NGC 1999 was discovered some two centuries ago by Sir William Herschel and his sister Caroline, and was cataloged later in the 19th century as object 1999 in the New General Catalogue.

These data were collected in January 2000 by the Hubble Heritage Team with the collaboration of star-formation experts C. Robert O'Dell (Rice University), Thomas P. Ray (Dublin Institute for Advanced Study), and David Corcoran (University of Limerick).(c) ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

This is a cutout from Euclid's full view of the Horsehead Nebula is a the resolution of the NISP instrument.

The full view of the Horsehead Nebula at the highest definition (VIS resolution) can be explored on ESASky.

Read more about Euclid’s view of the Horsehead Nebula