Fanerozoikum

| eon | éra | perioda | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fanerozoikum | kenozoikum | kvartér (čtvrtohory) | 3 | 3 |

| neogén | 23 | 20 | ||

| paleogén | 66 | 43 | ||

| mezozoikum (druhohory) | křída | 145 | 79 | |

| jura | 201 | 56 | ||

| trias | 252 | 51 | ||

| paleozoikum (prvohory) | perm | 299 | 47 | |

| karbon | 359 | 60 | ||

| devon | 419 | 60 | ||

| silur | 444 | 24 | ||

| ordovik | 485 | 42 | ||

| kambrium | 539 | 54 | ||

| proterozoikum (starohory) | neoproterozoikum | ediakara | 635 | 96 |

| kryogén | 720 | 85 | ||

| tonium | 1000 | 280 | ||

| mezoproterozoikum | 1600 | 600 | ||

| paleoproterozoikum | 2500 | 900 | ||

| archaikum (prahory) | 4031 | 1531 | ||

| hadaikum | 4567 | 536 | ||

Fanerozoikum (z řec. φανερός faneros, patrný, viditelný a ζωή zóé, život) je označení geologického období posledních přibližně 540 milionů let. Jedná se o dobu charakteristickou rozvinutými formami života na Zemi.

Fanerozoikum je nejmladší ze čtyř věků (eonů) Země a dále se dělí do tří velkých ér:

- paleozoikum (prvohory) – období prvotních živočichů

- mezozoikum (druhohory) – éra dinosaurů a plazů

- kenozoikum (třetihory a čtvrtohory) – éra savců

Starší dělení na čtyři „hory” tedy bylo redukováno na tři éry. Čtvrtohory pak byly zařazeny jako nižší geologická časová jednotka (geologická perioda) následující po paleogénu a neogénu, na které bylo rozděleno období tradičně označované jako třetihory.

Bouřlivý rozvoj života, kterým započalo fanerozoikum, se nazývá kambrická exploze. K dalším velkým událostem tohoto eonu, které proměnily život na Zemi, patřilo vymírání na konci permu a vymírání na konci křídy, které oddělují jednotlivé éry.

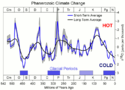

Průměrná teplota Země ve fanerozoiku byla přibližně 20 °C a pohybovala se od 10 °C do více než 25 °C, přičemž dnešní teplota je podprůměrná a rovna přibližně 14,5 °C.[2] Podle novější studie se průměrná teplota povrchu Země pohybovala v rozsahu 11 °C až 36 °C.[3] Z geologického hlediska je nyní díky zalednění stále doba ledová.

Reference

- ↑ Isotope Data - Jan Veizer [online]. mysite.science.uottawa.ca. Dostupné online. (anglicky)

- ↑ SCOTESE, Christopher. A new global temperature curve for the phanerozoic. S. 287167. www.researchgate.net [online]. 2016. S. 287167. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1130/abs/2016AM-287167. (anglicky)

- ↑ A 485-million-year history of Earth’s surface temperature. www.science.org [online]. [cit. 2024-10-27]. Dostupné online.

Externí odkazy

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Fanerozoikum na Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Fanerozoikum na Wikimedia Commons

| Geologický čas | ||

|---|---|---|

| Předchůdce: Proterozoikum | 542 Ma – dnešek Fanerozoikum | Nástupce: - |

Média použitá na této stránce

Autor: Dragons flight, Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

This figure shows the long-term evolution of oxygen isotope ratios during the Phanerozoic eon as measured in fossils, reported by Veizer et al. (1999), and updated online in 2004.[1] Such ratios reflect both the local temperature at the site of deposition and global changes associated with the extent of permanent continental glaciation. As such, relative changes in oxygen isotope ratios can be interpreted as rough changes in climate. Quantitative conversion between these data and direct temperature changes is a complicated process subject to many systematic uncertainties, however it is estimated that each 1 part per thousand change in δ18O represents roughly a 1.5-2 °C change in tropical sea surface temperatures (Veizer et al. 2000).

Also shown on this figure are blue bars showing periods when geological criteria (Frakes et al. 1992) indicate cold temperatures and glaciation as reported by Veizer et al. (2000). The Jurassic-Cretaceous period, plotted as a lighter blue bar, was interpreted as a "cool" period on geological grounds, but the configuration of continents at that time appears to have prevented the formation of large scale ice sheets.

All data presented here have been adjusted to 2004 ICS geologic timescale.[2] The "short-term average" was constructed by applying a σ = 3 Myr Gaussian weighted moving average to the original 16,692 reported measurements. The gray bar is the associated 95% statistical uncertainty in the moving average. The "long-term average" is a σ = 15 Myr Gaussian average of the short-term record (see notes).

On geologic time scales, the largest shift in oxygen isotope ratios is due to the slow radiogenic evolution of the mantle. A variety of proposals exist for dealing with this, and are subject to a variety of systematic biases, but the most common approach is simply to suppress long-term trends in the record. This approach was applied in this case by subtracting a quadratic polynomial fit to the short-term averages. As a result, it is not possible to draw any conclusion about very long-term (>200 Myr) changes in temperatures from this data alone. However, it is usually believed that temperatures during the present cold period and during the Cretaceous thermal maximum are not greatly different from cold and hot periods during most of the rest the Phanerozoic. However, recently this has been disputed by Royer et al. (2004), who suggest that the highs and lows in the early part of the Phanerozoic were both significantly warmer than their recent counterparts.

Common symbols for geologic periods are plotted at the top and bottom of the figure for reference.

- Long-term evolution

The long-term changes in isotope ratios have been interpreted as a ~140 Myr quasi-periodicity in global climate (Veizer et al. 2000) and some authors (Shaviv and Veizer 2003) have interpreted this periodicity as being driven by the solar system's motions about the galaxy. Encounters with galactic spiral arms can plausibly lead to a factor of 3 increase in cosmic ray flux. Since cosmic rays are the primary source of ionization in the troposphere, these events can plausibly impact global climate. A major limitation of this theory is that existing measurements can only poorly constrain the timing of encounters with the spiral arms.

The more traditional view is that long-term changes in global climate are controlled by geologic forces, and in particular, changes in the configuration of continents as a result of plate tectonics.