Kupa galaxií v Perseovi

| Kupa galaxií v Perseovi | |

|---|---|

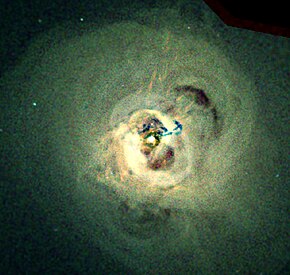

Rentgenový snímek střední části Kupy galaxií v Perseovi z rentgenové observatoře Chandra. Autor: NASA/CXC/IoA/A.Fabian et al. | |

| Pozorovací údaje (Ekvinokcium J2000,0) | |

| Rektascenze | 03h 19m 47,2s[1] |

| Deklinace | +41°30′47″[1] |

| Souhvězdí | Perseus (Per) |

| Vzdálenost | 240 Mly (73,6 Mpc)[1] |

| Fyzikální charakteristiky | |

| Počet galaxií | 190[1] |

| Nejjasnější galaxie | NGC 1275 |

| Označení v katalozích | |

| NGC 1275 Cluster, Perseus Cluster, Abell 426[1] | |

Kupa galaxií v Perseovi (také známá jako Abell 426) je kupa galaxií vzdálená přibližně 240 milionů světelných let[1] v souhvězdí Persea. Vzhledem ke Slunci má radiální rychlost 5 336 km/s a úhlový rozměr 863'.[1] Patří do Nadkupy galaxií Perseus–Pisces.[2] Jde o jeden z nejhmotnějších objektů ve známém vesmíru, který obsahuje tisíce galaxií obklopených ohromným oblakem plynu o teplotě několika milionů stupňů.

Rentgenové záření z kupy

Během přeletu rakety Aerobee 1. března 1970 byl v souhvězdí Persea objeven zdroj rentgenového záření, který byl označen jako Per XR-1 a později byl přiřazen ke galaxii NGC 1275 (Per A, 3C 84).[3] Jestliže je tímto zdrojem NGC 1275, pak má výkon Lx ~4 x 1045 ergs/s.[3] Podrobné pozorování satelitem Uhuru potvrdilo předchozí objev a souvislost s touto kupou galaxií.[4] Per X-1 je kupa galaxií 4U 0316+41 Označovaná jako Perseus cluster, Abell 426 a NGC 1275. Při pozorování v rentgenovém spektru jde o nejjasnější kupu galaxií.[5]

Kupa galaxií obsahuje rádiový zdroj 3C 84, který v současnosti vyhání bubliny relativistického plazmatu směrem k jádru kupy. Tyto bubliny můžeme na rentgenovém snímku vidět jako tmavé skvrny, protože odtlačují plyn, který vyzařuje rentgenové záření. Říká se jim také rádiové bubliny, protože kvůli relativistickým částicím vysílají rádiové vlny. Galaxie NGC 1275 se nachází uprostřed kupy, kde je rentgenové záření nejsilnější.

Galerie obrázků

Kupa galaxií v Perseovi na snímku z observatoře Chandra.

Víry mohou kupě galaxií bránit v ochlazování.

Reference

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Perseus cluster na anglické Wikipedii.

- ↑ a b c d e f g NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database: Results for Abell 426 [online]. [cit. 2016-08-19]. Dostupné online. (anglicky)

- ↑ Richard Powell. Atlas of the Universe: The Nearest Superclusters [online]. [cit. 2016-08-19]. Dostupné online. (anglicky)

- ↑ a b Fritz, G.; Davidsen, A.; Meekins, J. F., et al. Discovery of an X-ray source in Perseus. S. L81–5. Astrophysical Journal [online]. Březen 1971 [cit. 2016-08-19]. Roč. 164, čís. 3, s. L81–5. DOI 10.1086/180697. Bibcode 1971ApJ...164L..81F. (anglicky)

- ↑ Forman, W.; Kellogg, E.; Gursky, H., et al. Observations of the Extended X-Ray Sources in the Perseus and Coma Clusters from UHURU. S. 309–316. Journal of Astrophysics [online]. Prosinec 1972 [cit. 2016-08-19]. Roč. 178, s. 309–316. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1086/151791. Bibcode 1972ApJ...178..309F. (anglicky)

- ↑ Edge, A. C.; Stewart, G. C.; Fabian, A. C. Properties of cooling flows in a flux limited sample of clusters of galaxies. S. 177. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society [online]. Září 1992 [cit. 2016-08-19]. Roč. 258, s. 177. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1093/mnras/258.1.177. Bibcode 1992MNRAS.258..177E. (anglicky)

Související články

Externí odkazy

- NED – Abell 426

- APOD (2011-07-12) – "The Perseus Cluster of Galaxies"

- Brunzendorf, J.; Meusinger, H. The galaxy cluster Abell 426 (Perseus). A catalogue of 660 galaxy positions, isophotal magnitudes and morphological types. S. 141–161. Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement [online]. Říjen 1999 [cit. 2016-08-19]. Roč. 139, s. 141–161. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1051/aas:1999111. Bibcode 1999A&AS..139..141B. (anglicky)

Média použitá na této stránce

A new study of the central region of the Perseus galaxy cluster, shown in this image, using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and 73 other clusters with ESA's XMM-Newton has revealed a mysterious X-ray signal in the data. This signal is represented in the circled data points in the inset, which is a plot of X-ray intensity as a function of X-ray energy. The signal is also seen in over 70 other galaxy clusters using XMM-Newton. This unidentified X-ray emission line - that is, a spike of intensity at a very specific energy, in this case centered on about 3.56 kiloelectron volts (keV) - requires further investigation to confirm both the signal's existence and nature as described in the latest Chandra press release.

One intriguing possible explanation of this X-ray emission line is that it is produced by the decay of sterile neutrinos, a type of particle that has been proposed as a candidate for dark matter. While holding exciting potential, these results must be confirmed with additional data to rule out other explanations and determine whether it is plausible that dark matter has been observed.

There is uncertainty in these results, in part, because the detection of this emission line is pushing the capabilities of both Chandra and XMM-Newton in terms of sensitivity. Also, there may be explanations other than sterile neutrinos if this X-ray emission line is deemed to be real. For example, there are ways that normal matter in the cluster could have produced the line, although the team's analysis suggested that all of these would involve unlikely changes to our understanding of physical conditions in the galaxy cluster or the details of the atomic physics of extremely hot gases.

This image is Chandra's latest view of hot gas in the central region of the Perseus Cluster, where red, green, and blue show low, medium, and high-energy X-rays respectively. It combines data equivalent to more than 17 days worth of observing time taken over a decade with Chandra. The Perseus Cluster is one of the most massive objects in the Universe, and contains thousands of galaxies immersed in an enormous cloud of superheated gas. In Chandra's X-ray image, enormous bright loops, ripples, and jet-like streaks throughout the cluster can be seen. The dark blue filaments in the center are likely due to a galaxy that has been torn apart and is falling into NGC 1275 (a.k.a. Perseus A), the giant galaxy that lies at the center of the cluster.October 27, 2014

RELEASE 14-296 NASA’S Chandra Observatory Identifies Impact of Cosmic Chaos on Star Birth

IMAGE:

Chandra observations of the Perseus and Virgo galaxy clusters suggest turbulence may be preventing hot gas there from cooling, addressing a long-standing question of galaxy clusters do not form large numbers of stars.

DESCRIPTION:

The same phenomenon that causes a bumpy airplane ride, turbulence, may be the solution to a long-standing mystery about stars’ birth, or the absence of it, according to a new study using data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the universe, held together by gravity. These behemoths contain hundreds or thousands of individual galaxies that are immersed in gas with temperatures of millions of degrees.

This hot gas, which is the heftiest component of the galaxy clusters aside from unseen dark matter, glows brightly in X-ray light detected by Chandra. Over time, the gas in the centers of these clusters should cool enough that stars form at prodigious rates. However, this is not what astronomers have observed in many galaxy clusters.

“We knew that somehow the gas in clusters is being heated to prevent it cooling and forming stars. The question was exactly how,” said Irina Zhuravleva of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, who led the study that appears in the latest online issue of the journal Nature. “We think we may have found evidence that the heat is channeled from turbulent motions, which we identify from signatures recorded in X-ray images.”

Prior studies show supermassive black holes, centered in large galaxies in the middle of galaxy clusters, pump vast quantities of energy around them in powerful jets of energetic particles that create cavities in the hot gas. Chandra, and other X-ray telescopes, have detected these giant cavities before.

The latest research by Zhuravleva and her colleagues provides new insight into how energy can be transferred from these cavities to the surrounding gas. The interaction of the cavities with the gas may be generating turbulence, or chaotic motion, which then disperses to keep the gas hot for billions of years.

“Any gas motions from the turbulence will eventually decay, releasing their energy to the gas,” said co-author Eugene Churazov of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Munich, Germany. “But the gas won’t cool if turbulence is strong enough and generated often enough.”

The evidence for turbulence comes from Chandra data on two enormous galaxy clusters named Perseus and Virgo. By analyzing extended observation data of each cluster, the team was able to measure fluctuations in the density of the gas. This information allowed them to estimate the amount of turbulence in the gas.

“Our work gives us an estimate of how much turbulence is generated in these clusters,” said Alexander Schekochihin of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. “From what we’ve determined so far, there’s enough turbulence to balance the cooling of the gas.

These results support the “feedback” model involving supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxy clusters. Gas cools and falls toward the black hole at an accelerating rate, causing the black hole to increase the output of its jets, which produce cavities and drive the turbulence in the gas. This turbulence eventually dissipates and heats the gas.

While a merger between two galaxy clusters may also produce turbulence, the researchers think that outbursts from supermassive black holes are the main source of this cosmic commotion in the dense centers of many clusters.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

An interactive image, podcast, and video about these findings are available at: http://chandra.si.edu

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/chandraAn accumulation of 270 hours of Chandra observations of the central regions of the Perseus galaxy cluster reveals evidence of the turmoil that has wracked the cluster for hundreds of millions of years. One of the most massive objects in the universe, the cluster contains thousands of galaxies immersed in a vast cloud of multimillion degree gas with the mass equivalent of trillions of suns.

Enormous bright loops, ripples, and jet-like streaks are apparent in the image. The dark blue filaments in the center are likely due to a galaxy that has been torn apart and is falling into NGC 1275, a.k.a. Perseus A, the giant galaxy that lies at the center of the cluster.

Image is 284 arcsec across. RA 03h 19m 47.60s Dec +41° 30' 37.00" in Perseus. Observation dates: 13 pointings between August 8, 2002 and October 20, 2004. Color code: Energy (Red 0.3-1.2 keV, Green 1.2-2 keV, Blue 2-7 keV). Instrument: ACIS.