Titanoboa

Stratigrafický výskyt: Paleocén, asi před 60 miliony let | |

|---|---|

Titanoboa - přibližný vzhled | |

V porovnání s člověkem (modrý had) | |

| Vědecká klasifikace | |

| Říše | živočichové (Animalia) |

| Kmen | strunatci (Chordata) |

| Třída | plazi (Reptilia) |

| Řád | šupinatí (Squamata) |

| Čeleď | hroznýšovití (Boidae) |

| Rod | Titanoboa Head, 2009 |

| Druhy | |

| |

| Některá data mohou pocházet z datové položky. | |

Titanoboa cerrejonensis byl druh obřího hroznýšovitého hada, žijícího v období paleocénu na území současné Kolumbie.

Objev

Fosilie tohoto hada byly v podobě několika obřích obratlů (holotyp s katalogovým označením UF/IGM 1) objeveny v lokalitě lomu La Puente (Carbon Cerrejón; uhelný důl Cerrejón). Před 62 až 58 miliony let se jednalo o záplavovou nížinu s bohatou tropickou vegetací, ve které žili tito obří hadi a množství dalších živočichů (ryby, želvy, další hadi, krokodýli i různí savci a ptáci). Jméno Titanoboa znamená „Titánský škrtič“, slovo boa označuje škrtiče z příbuzenstva krajt a hroznýšů.[1]

Popis

Jedná se o největšího dosud známého hada v dějinách života na Zemi. Byl formálně popsán v roce 2009 podle nálezu z paleocénních vrstev Kolumbie.[2] Žil před asi 60 miliony let v tropickém prostředí a lovil zde menší a středně velké obratlovce. S největší pravděpodobností se specializoval na ryby.[3]

Tento obří had měřil na délku údajně asi 12,8 až 14,8 metru[4] a jeho hmotnost se mohla pohybovat kolem 1,1 tuny.[5] Byl tedy zhruba o 3 metry delší, než největší do té doby známý had z třetihorního období eocénu, rod Gigantophis.

Systematika

T. cerrejonensis spadal podle provedené fylogenetické analýzy do čeledi Boidae a podčeledi Boinae, tedy mezi hroznýšovité hady. Mezi jeho blízké příbuzné patřily nebo patří rody Acrantophis, Bavarioboa, Boa, Boavus a další.[6]

Galerie

Reference

- ↑ Největší had na světě polykal krokodýly zaživa. Víte, jak se jmenoval?. Zoom magazin [online]. [cit. 2021-12-02]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ HEAD, Jason J.; BLOCH, Jonathan I.; HASTINGS, Alexander K., a kol. Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures. Nature. 2008-10-28, čís. 457, s. 715–717. Dostupné online [cit. 2009-02-05]. DOI 10.1038/nature07671. (anglicky)

- ↑ HEAD, Jason J., a kol. Cranial osteology, Body Size, Systematics, and Ecology of the giant Paleocene Snake Titanoboa cerrejonensis. Conference: 73nd Annual Meeting of the Society of vertebrate Paleontology [online]. 2013 [cit. 2020-09-27]. Dostupné online. (anglicky)

- ↑ http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/t/titanoboa.html

- ↑ https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=114112

- ↑ Szyndlar, Z. and Schleich, H. H. (1993). Description of Miocene snake from Petersbuch 2 with comments on the lower and middle Miocene ophidian faunas of southern Germany. Stuttgarter Beitrage zur Naturkunde, Series B. Geologie und Palaontologie, 192: 1-47.

Externí odkazy

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Titanoboa na Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Titanoboa na Wikimedia Commons  Taxon Titanoboa ve Wikidruzích

Taxon Titanoboa ve Wikidruzích- Článek na webu NatGeo (anglicky)

- Článek na webu Darwins Door (anglicky)

- Článek na webu DinosaurusBlog (česky)

- Video o rodu Titanoboa (anglicky)

- Profil na databázi Fossilworks[nedostupný zdroj] (anglicky)

Média použitá na této stránce

Autor:

- Information-silk.png: Mark James

- derivative work: KSiOM(Talk)

A tiny blue 'i' information icon converted from the Silk icon set at famfamfam.com

Autor: Nobu Tamura email:nobu.tamura@yahoo.com www.palaeocritti.com, Licence: CC BY 3.0

Titanoboa.

Autor: Gamma 124, Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0

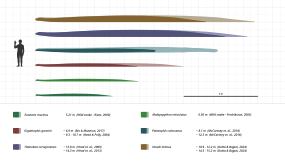

: A size comparison of various snakes living and extinct. Comparing large individuals of the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) and reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) to length estimates of the extinct Palaeophis colossus, Gigantophis garstini, Vasuki indicus and Titanoboa cerrejonensis.

- There is often uncertainty over the maximum size possible or the largest reliably recorded individuals for living animal species, generally due to unreliable visual estimations or lack of hard evidence. Accurately measuring the overall length of a snake is difficult. Various methods exist, but all have issues.[1][2] Therefore, researchers might disagree with what they consider the largest reliable recorded size for a given species, and/or the sizes shown here might not represent the true maximum for the species. It is also important to note that the largest recorded sizes often represent exceptional individuals and do not represent the species average adult size.

- • The green anaconda is generally considered the most massive extant snake. The silhouette is scaled to 5.21 metres (17.1 ft), the longest individual out of ~780 anacondas measured around a cattle ranch by Jesús Antonio Rivas. There are reports of exceptionally large anacondas, some claimed up to 9 to 11 metres (30 to 36 ft), but these are controversial.[1][3][4][2] Rivas cast doubt on the existence of exceptionally large anacondas due to factors such as constraints on body size and breeding ability. However, they suggested that sizes larger than those observed in the study area may be possible in habitats with permanent water bodies and little human intervention.[2] In 2024, a large anaconda was found dead in Bonito, Brazil, which was initially measured around 6.45 metres (21.2 ft) by a rope and later reportedly measured more precisely at 6.32 metres (20.7 ft). However, this has yet to be formally published.[5][6][7]

- • The reticulated python is considered the longest extant snake but is usually less massive relative to the green anaconda. The silhouette is scaled to 6.95 metres (22.8 ft), which is the length of a reliably measured wild reticulated python.[8] Larger sizes have been reported, some claims reach up to ~10 metres (33 ft) in length, but these are considered controversial or unreliable.[3][4][8] A captive reticulated python named "Medusa" was reported to measure 7.67 metres (25.2 ft).[9]

- Extinct snakes are often known from fragmentary remains, so length estimates must be extrapolated using living species or more complete relatives. However, due to the large number of variables, these estimates can vary substantially between methods and should be treated with caution. Due to the lack of complete remains, the morphology of the extinct snakes is uncertain. P. colossus has been restored here with a small paddle at the end of the tail, a feature common in marine snakes. However, due to lack of remains this feature is speculative. Skull material is uncommon for fossil snakes. The heads of Gigantophis and Vasuki are inspired by a composite skull diagrams of Madtsoiidae snakes, Wonambi and Yurlunggur.[10]

- • Gigantophis garstini is a large member of the extinct snake family Madtsoiidae. Gigantophis is known from numerous vertebrae. In 2004, it was estimated between ~9.3 and 10.7 metres (31 and 35 ft) in length by Jason Head & P. David Polly using regression analysis (10 metres (33 ft) shown here). A later study by Jonathan P. Rio & Philip D. Mannion used a regression analysis that compared the vertebral postzygapophyseal width to the total length in extant boine snakes. This regression estimated the largest vertebra of the Gigantophis type specimen at ~6.9 metres (23 ft) (+/- 0.3 m). However, the authors urged caution due to uncertainties regarding the possible position of the vertebra in the spinal column, the lack of articulated madtsoiid remains, and the possibility that Gigantophis and extant boine snakes differ in the relationship between postzygapophyseal width and total length.[11][12]

- • Palaeophis colossus is an extinct species of marine snake in the family Palaeophiidae. One vertebra, CNRST-SUNY 290, produced a length estimate of 8.1 metres (27 ft), comparing the trans-prezygapophyseal width to a variety of extant snake species. Using a different vertebral landmark of another vertebra, the the cotylar width of NHMUK PV R 9870, produced a length estimate of 12.3 metres (40 ft).

- • Titanoboa cerrejonensis is an extinct boid only known from large vertebrae and skull material, but size estimates suggest it is one of the largest snakes known. In 2009, Jason Head and colleagues estimated it at ~12.8 metres (42 ft) (+/-2.18 m) by regression analysis that compared vertebral width against body lengths for extant boine snakes. In a later conference abstract, Head et al. estimated a length of ~14.3 metres (47 ft) (+/-1.28 m) based on skull material and comparisons to anacondas.[13][14]

- • Vasuki indicus is a large Madtsoiidae snake known from several large vertebrae. Datta & Bajpai applied two existing length estimation regressions on these vertebrae, producing estimates ranging from 10.9 and 12.2 metres (36 and 40 ft) and 14.5 and 15.2 metres (48 and 50 ft) (11.5 and 14.8 metres (38 and 49 ft) shown here).[15] However, due to the incompleteness of the remains and limited knowledge of Madtsoiidae snake vertebral columns, Datta & Bajpai urged caution with the estimates.

- • Human scaled to 180 cm (5 ft 11 in).

References

- ↑ a b Wood, Gerald (1983) The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats ISBN: 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ a b c Rivas, Jesús Antonio (2000) The life history of the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), with emphasis on its reproductive Biology (Ph.D.)[1] (PDF), University of Tennessee, archived from the original on 2016-03-03 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ a b G Barker, David (2012). "The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a New Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus". Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 47: 165-168.

- ↑ a b Murphy, John C. (2015). Size Records for Giant Snakes. squamates.blogspot.com. Retrieved on February 17, 2020.[dead link]

- ↑ BREAKING: met enorm veel pijn in mijn hart wil ik laten weten dat de machtige grote groene anaconda waar ik mee gezwommen heb dit weekend dood is aangetroffen in de rivier…. www.instagram.com. Retrieved on 2024-03-28.

- ↑ MAIOR SUCURI DO MUNDO JÁ MEDIDA GIGANTESCAOVOZONA 6.45 METROS. www.instagram.com. Retrieved on 2024-03-28.

- ↑ Nenhuma perfuração foi achada na sucuri morta em Bonito (MS), diz delegado. Retrieved 2024-03-31 – via www.youtube.com.

- ↑ a b Fredriksson, G. M. (2005). "Predation on Sun Bears by Reticulated Python in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 53 (1): 165–168. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved on 2019-04-24.

- ↑ Longest snake in captivity ever. Guinness World Records (12 October 2011). Retrieved on February 17, 2020.

- ↑ Palci, Alessandro (March 2018). "Palaeoecological inferences for the fossil Australian snakesYurlunggurandWonambi(Serpentes, Madtsoiidae)". Royal Society Open Science 5 (3): 172012. DOI:10.1098/rsos.172012. ISSN 2054-5703.

- ↑ Head, J. (2004). "They might be giants: morphometric methods for reconstructing body size in the world's largest snakes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (Supp. 3): 68A–69A. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643.

- ↑ (2017). "The osteology of the giant snake Gigantophis garstini from the upper Eocene of North Africa and its bearing on the phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of Madtsoiidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37 (4): e1347179. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2017.1347179.

- ↑ Head, Jason J. (2009). "Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures". Nature 457 (7230): 715–717. DOI:10.1038/nature07671. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ↑ Head, Jason (2013). "Cranial osteology, Body Size, Systematics, and Ecology of the giant Paleocene Snake Titanoboa cerrejonensis". Conference: 73nd Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology: 140-141.

- ↑ Datta, Debajit (2024-04-18). "Largest known madtsoiid snake from warm Eocene period of India suggests intercontinental Gondwana dispersal". Scientific Reports 14 (1). DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-58377-0. ISSN 2045-2322.