Willoughby Wallace Hooper

| Willoughby Wallace Hooper | |

|---|---|

| Narození | 4. února 1837 Kennington |

| Úmrtí | 21. dubna 1912 (ve věku 75 let) Kilmington |

| Povolání | fotograf |

| Některá data mohou pocházet z datové položky. Chybí svobodný obrázek. | |

Willoughby Wallace Hooper (1837, Londýn – 21. dubna 1912, Kilmington poblíž Axminsteru v Anglii) byl anglický vojenský fotograf. Během britské okupace se stal známý svými fotografiemi obyvatel Barmy a Indů. Hooper přispěl základním vizuálním materiálem pro etnicky – rasistické osmidílné dílo The People of India (publikováno 1868–1875). Dokumentoval hladomor v Indii v letech 1876–1879, pořizoval portréty hladovějících lidí upravené ve stylu buržoazních rodinných fotografií. Jeho fotografie indického lovu tygrů zdobily pouliční lampy v Anglii. V roce 1886 se Hooper dostal pod vlnu kritiky veřejnosti poté, co zdokumentoval[1] a zveřejnil fotografii z popravy povstalců v Mandalaji.

Životopis

Willoughby Wallace Hooper byl synem Thomase a Marie Hooperových z Brixtonu. Dne 19. května 1837 byl pokřtěn v kostele svatého Marka v Kenningtonu. Po ukončení školy v Ramsgate nastoupil v roce 1853 na pozici sekretáře v East India House. V roce 1858 byl povolán do lehké kavalérie v Indii, v roce 1859 se stal poručíkem a nakonec v roce 1884 podplukovníkem. V roce 1896 odešel do důchodu a zemřel svobodný v roce 1912 v Devonu v jihozápadní Anglii.

Po třetí britsko-barmské válce v roce 1885 byla Barma zcela podmaněna Velkou Británií a 1. ledna 1886 se stala součástí Britské Indie. Poslední barmský král, Thibaw Min, byl se svou rodinou vyhoštěn britskou okupací v Indii,[2] kde také zemřel. Koloniální správa narazila na obrovský odpor Barmánců masivními vyhlazovacími kampaněmi proti celým vesnicím a městům.

Jako amatérský fotograf měl Hooper při nástupu do práce svůj fotoaparát. Členové vedení 7. Kavalérie Madras, ke které patřil, si brzy uvědomili jeho talent a propustili ho z vojenské služby. Hooperovy fotografie ocenil také generální guvernér a místopředseda britské Indie Lord Canning. Od té doby Hooper cestoval s vojáky a stal se jejich vojenským fotografem. Asi v roce 1870 založil spolu se svým kolegou Georgem Westernem společnost Hooper and Western, aby mohl své fotografie prodávat. Dvanáctidílná série „Tiger Shooting“, lovu tygrů z doby kolem roku 1872 byla velkým prodejním úspěchem. Přesto Hooper zůstal u armády. Stále častěji se věnoval sociálním otázkám, například hladomoru v roce 1878. Jeho perspektiva vždy byla z pohledu koloniálních vládců, kteří se dívají dolů na exotické, podřadné lidi. Anglický satirický časopis Punch publikoval karikaturu Hoopera s hladovějícími lidmi, s poznámkou, že při vytváření „krásných“ portrétních kompozic nejevil nebohým žádnou náklonnost.

Fotografie popravy v Mandalaji

Díky technologii citlivějších fotografických desek chtěl během programu „WW Hooper“ zaznamenávat scény s krátkými expozičními časy. Zúčastnil se 3. Barmské války v letech 1885–1886 jako policista (probošt Marshall) a zažil prudký odpor místních bojovníků. Došlo k mnoha popravám. Hooper vnímal fotografie z popravy zastřelením vězňů jako vhodné pro vyčerpání jeho krátkých expozičních časů a pořízení dosud nezaznamenaného dokumentu doby. Podle jeho vlastního popisu chtěl ukázat obličejové rysy a výrazy mužů vteřinu před tím, než je zasáhnou kulky.

Jeho fotografie popravy povstaleckých Barmánců v Mandalaji počátkem roku 1886[3] způsobila rozruch u vojáků, ale také v politických kruzích ve Velké Británii. Mimo jiné se o této události diskutovalo ve sněmovně 23. února a vojenské slyšení proběhlo 19. března, kde Hooper mimo jiné argumentoval tím, že byl na popravě v civilu. Místokrál indické kolonie, Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, vznesl proti němu vážné obvinění.

Byl obviněn ze dvou samostatných trestných činů. Nejprve se pokusil přimět vězně k přiznání tím, že se mu vyhrožoval popravou. Za druhé – a mnohem závažnější – Hooper se domlouval se střelci z popravčí čety, že by měli vložit menší zpoždění před povelem „pal!“, aby mohl sundat krytku z objektivu. Expoziční čas byl řízen sundáním a nasazením krytky objektivu. Na jednání Hooper všechno popřel a sdílel svůj názor s redakcí Times:

- „Fotoaparát byl instalován na místo před příchodem vězňů ke zdi.“ Měli zavázané oči, takže o fotoaparátu nemohli vědět. Slova příkazu k palbě nebyla v žádném případě načasována takovým způsobem, aby stačila k odhalení desky, protože k tomu došlo bez prodlení. Slova rozkazu Kommandos ‚Připravit! Pozor! Pal!‘ byly dány hlavním důstojníkem v souladu s předpisy pro popravu zastřelením a mezi slovy ‚Pozor!‘ a ‚Pal!‘ nebylo žádné zpoždění.“

Aby zdůraznil význam fotografie pro potomky, Hooper uzavřel diskusi slovy:

- „Ještě nikdo před tím se vyfotografovat popravu nepokusil.“[4]

Zpravodaj Rangoon Gazette a London Gazette řekl před měsícem novinářům Times, že byl svědkem popravy, a viděl, jak před rozkazem „Pal!“ udělalo komando několik sekund pauzu, ve které “nadšený amatérský fotograf„ odstranil krytku z objektivu.[5]

Na vojenském slyšení byl Hooper uznán jako vinen. Důsledkem bylo pozastavení jeho služby, ale díky jeho „velkým zásluhám“ jako důstojníka v koloniální válce to znamenalo prakticky oficiální napomenutí a dočasné snížení platu.[6]

Po tomto případu skončila kariéra „plukovníka Hooperse“.

Publikace

- The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan. (Lidé v Indii: Série fotografických ilustrací ras a kmenů Hindustánu s popisným knihtiskem), 8 svazků s mnoha Hooperovými fotografiemi. Londýn 1868–1875

- Burmah: a series of one hundred photographs. Londýn 1887

- Lantern Readings illustrative of the Burmah Expeditionary Force and manners and customs of the Burmese. Londýn; Derby 1887

- Lantern reading: Tiger shooting in India, Londýn 1887

Galerie

- Lidé trpící hladomorem, asi 1877

- Forsaken, asi 1877

- Lidé trpící hladomorem, asi 1877

- Genocida hladomoru v Indii pod britskou koloniální nadvládou, skupina vyhublých žen, Bangalore

- Genocida hladomoru v Indii pod britskou koloniální nadvládou, Madras

- Lov tygrů v Britské Indii, pytláci chtějí hlavně trofeje – kůži a hlavu

- Sikh z Indie, 1860–1870

- Pekařský obchod, čínská čtvrť Mandalaj

- Thipoa Min byl posledním králem barmské dynastie Konbaung (Myanmar) a také posledním barmským panovníkem v dějinách země. Jeho vláda skončila, když Barma byla poražena silami Britského impéria ve třetí anglo-barmské válce, dne 29. listopadu 1885, před oficiální anexí dne 1. ledna 1886. Na snímku je král Thipoa, královna Supayalat (?) a její sestra princezna Supayaji (?), listopad 1885.

- Královský člun krále Thipoa, Mandalaj

Odkazy

Reference

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Willoughby Wallace Hooper na německé Wikipedii.

- ↑ HANNAVY, John. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. [s.l.]: Routledge 1629 s. Dostupné online. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1. (anglicky) Google-Books-ID: Kd5cAgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Who stole Burma’s royal ruby? (BBC), 2. listopadu 2017

- ↑ Grattan Geary: Burma, after the conquest: viewed in its political, social, and commercial aspects, from Mandalay. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London 1886, s. 241–243

- ↑ Hooper pro Times 2. března 1886, vytisknuto ve vydání 4. března, s. 5

- ↑ The Times, 4. 3. 1886, s. 5. Der Artikel über Vorfälle in den asiatischen Kolonien schließt mit der Kritik eines französischen Kaufmanns, dass die Polizei am 16. Januar 1886 sechs unbekleidete Tote durch den Markt von Mandalay auf dem Weg zum Friedhof getragen hätten.

- ↑ The Times: The Charges Against Colonel Hooper, 8. 9. 1886, s. 3

Literatura

- John Hannavy (vyd.): Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography (Encyklopedie fotografie devatenáctého století), s. 713 f. Taylor & Francis 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-97235-2

- Typická Hooperova fotografie – vedle mnoha dalších v Britské knihovně: Mindhla after its capture Archivováno 1. 4. 2021 na Wayback Machine.

- Záznam v rejstříku fotografů RCS Archivováno 23. 7. 2019 na Wayback Machine.

- Reference Oxford University Press Archivováno 9. 4. 2016 na Wayback Machine.

Související články

- Fotografie v Indii

- Fotografie v Myanmaru

Další významní fotografové 19. století v Barmě:

- John McCosh

- Willoughby Wallace Hooper

- Felice Beato

- Philip Adolphe Klier

- Max Henry Ferrars

- Alexander Greenlaw

- Edmund David Lyon

Externí odkazy

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Willoughby Wallace Hooper na Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Willoughby Wallace Hooper na Wikimedia Commons

Média použitá na této stránce

Photograph of King Thibaw’s State Barge on the moat at Mandalay in Burma (Myanmar), taken by Willoughby Wallace Hooper in 1885.

- The photograph is from a series documenting the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885-86) made by Hooper while serving as Provost Marshal with the British army. Thibaw was the last king of Burma and ruled from 1878 until 1885, when he was deposed and exiled to India by the British. The Burma Expeditionary Force entered Mandalay, the Burmese royal capital, on 28 November, beginning an occupation of the city, and the war culminated in the annexation of Upper Burma by the British on 1 January 1886.

- Burmese state barges were magnificent gilded vessels roofed by a tiered spire (pyatthat) denoting sacred royal space, and a prow in the form of a mythical beast or celestial spirit. They were used by kings, courtiers and high officials in spectacular ceremonial processions and water festivals. At Mandalay the barge was moored on the moat which surrounded the city.

- Hooper describes the barge and the use to which it was put during the occupation in a caption accompanying the photograph: “This is a very gorgeous affair, the whole of it is gilded over, and it has a wonderful looking prow in the form of an eagle. The usual bits of looking glass have not been omitted in its decoration. Theebaw and his Queen used to be towed round the moat in this, on some of the rare occasions when he ventured out of the palace enclosure. It is now moored alongside the berm near the N.E. corner of the city, where the 'Gymkhana' sports of the Garrison are held, and serves as a refreshment room, a very necessary adjunct to any athletic sports in the tropics.”

- Hooper was a dedicated amateur photographer and his photographs of the war in Burma are considered “one of the most accomplished and comprehensive records of a nineteenth century military campaign”. They were published in 1887 as ‘Burmah: a series of one hundred photographs illustrating incidents connected with the British Expeditionary Force to that country, from the embarkation at Madras, 1st Nov, 1885, to the capture of King Theebaw, with many views of Mandalay and surrounding country, native life and industries’. There were two editions, one with albumen prints, one with autotypes, and a set of lantern slides was issued. The series is also notable for the political scandal which arose following allegations by a journalist that Hooper had acted sadistically in the process of photographing the execution by firing squad of Burmese rebels. The subsequent court of inquiry concluded that he had behaved in a “callous and indecorous” way and the affair raised issues of the ethical role of the photographer in documenting human suffering and the conduct of the British military during a colonial war.

Photograph of a baker’s shop in the Chinese quarter of Mandalay in Burma (Myanmar), taken by Willoughby Wallace Hooper in 1886. The war culminated in the annexation of Upper Burma by the British on 1 January 1886. Chinese communities had existed for many centuries in rural Burma and were largely formed by migrants travelling overland from China into Burma along the north-eastern trade routes. The urban Chinese population originated during the colonial era when Chinese from the coastal provinces of China came by sea to work as merchants, among other professions. The Chinese quarter in Mandalay was near the King’s Bazaar, on the south side of B Road. A caption by Hooper accompanying the photograph describes the shop: “It is not perhaps a very inviting looking place, nevertheless the bread made in Mandalay is exceedingly good. Bread is much eaten by the Burmese, besides various kinds of cakes and chupatties, a sort of pancake or girdlecake: the man on the left is making one of these while the other man is tending the pot over the furnace.”

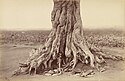

A view of a water buffalo being tethered as bait for a tiger

Autor: unknown, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Famine in Bangalore, India: a group of emaciated women and children. Photograph, 1876/1878.

Iconographic Collections

Keywords: FAMINE; bangalore; Starvation; India

1876-1879 famine in India

Digby estimated 10.3 million people starved to death most of which were in South India (some refer to the tragedy as the Madras famine). Maharatna estimated 8.2 million died from hunger and diseases that followed. British colonial rule argued that famine relief would be an inappropriate response and encourage laziness. Some officials argued the Thomas R Malthus theory that famines are a nature's way for population control and argued British government should not intervene. British government continued its policy of "forced export" of food from India in 1876-1879, while the famine swept among its people.

The poverty, misery and diseases wiped out villages and families. Some farmers and their families committed suicide during this 3 year period from the trauma and the extended period of starvation. Parents killed themselves so that their children could eat the remaining scraps of food, creating a pool of abandoned and foresaken children.

Photograph by Willoughby Wallace Hooper

For more on the famine, see Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, by Mike DavisBurmese Dacoits Readied for Execution

Photograph by Willoughby Wallace Hooper

Hunting a tiger was a sport for British officials in colonial India. This 1876-1877 AD photograph shows a wild tiger after it was shot and while it was being cut open for its skin and head trophy.

While these sports were in vogue, one of numerous famines of 19th century ravaged India. In the year when this tiger trophy was killed for pleasure, Digby estimated 10.3 million Indian people starved to death most of which were in South India; Maharatna estimated 8.2 million died. British colonial rule argued that famine relief would be an inappropriate response and would encourage laziness, and the Malthus theory that famine is nature's way of population control. The poverty, misery and diseases wiped out villages and families. Some farmers and their families committed suicide after suffering the trauma and the extended period of starvation. Parents killed themselves so that their children could eat the remaining scraps of food, creating a pool of abandoned and foresaken children.

The 19th century colonial rule was a period of widespread inequality in India.

For more on the famine, see Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, by Mike DavisKing Thibaw, Queen Supayalat and her sister Princess Supayaji, made from a negative found in the Royal Palace, Mandalay.

Inmates of a relief camp (during the famine 1876-1878) in Madras - Tamil Nadu - South India

1876-1879 famine in India

Digby estimated 10.3 million people starved to death most of which were in South India (some refer to the tragedy as the Madras famine). Maharatna estimated 8.2 million died from hunger and diseases that followed. British colonial rule argued that famine relief would be an inappropriate response and encourage laziness. Some officials argued the Thomas R Malthus theory that famines are a nature's way for population control and argued British government should not intervene. British government continued its policy of "forced export" of food from India in 1876-1879, while the famine swept among its people.

The poverty, misery and diseases wiped out villages and families. Some farmers and their families committed suicide during this 3 year period from the trauma and the extended period of starvation. Parents killed themselves so that their children could eat the remaining scraps of food, creating a pool of abandoned and foresaken children.

Photograph by Willoughby Wallace Hooper (1876-1879)

For more on the famine, see Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, by Mike Davis"A Sikh", 1860s photograph